Experience the History of Stockton, California's Filipino Community: A Trip Through Time

A look back at the immigration of Filipinos in California, the tribulations forced upon them, and how they continue to thrive in a city built on resilience.

The Filipino people are a vital part of the Stockton community. One of the predominant Asian cultures within our city, their history—not only in this nation but also in this city—is a testament to the resilience within the lifeline of Port City. However, to celebrate this community like many others, we must go back and understand their trials and tribulations within this nation and our city limits.

After the Spanish-American War and the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1898, Spain ceded the Philippines to the United States. For the next four years, the Philippine-American War would devastate the country, killing 20,000 Filipinos and leaving another 200,000 to die from famine and disease. When that war ended, the Supreme Court gave Congress the power to determine the status of newly acquired territories, giving the US the green light to pursue colonialism throughout the Pacific. Under the control of the United States, Filipinos received the title of “US nationals,” placing US allegiance upon them, but without the full rights of citizenship.

With that came an influx of Filipino migration to the United States. By 1920, the Filipino population in the nation was over 26,000. With their arrival came the anti-Filipino sentiment of US citizens. Many tried to enact the Alien Land Law and the Johnson-Reed Immigration Act (the Asian Exclusion Act) to prohibit those of Asian descent from owning land. However, since Filipino immigrants were considered US nationals, they technically were exempted from the restrictions that others of Asian descent were facing. However, bigoted citizens would continue to inflict hate and violence against them.

Filipino immigrants faced constant bigotry in the ‘20s & ‘30s, reaching a high point of extremism in 1929 and 1930. A race riot erupted in Exeter with white men attacking Filipinos throughout the town, ranches destroyed, a labor camp in Dinuba firebombed, and bunkhouses in Arvin shot at. It reached its peak in January 1930, when the city of Watsonville experienced racial riots with violent assaults on Filipino farm workers by hundreds of white men. These acts of bigoted violence would often leave behind signs reading “Get rid of all Filipinos or we’ll burn this town down.” This violence would make its way to Stockton and San Francisco.

With the Tydings-McDuffee Act of 1934 promising to give independence to the Philippines within ten years, the US reverted Filipinos from “nationals” to “resident aliens,” capping Filipino immigration at only 50 per year. A year later, FDR’s administration offered Filipinos an all-expense-paid trip back to the Philippines under the condition that they never return. Of the over 45,000 Filipinos in the US (30,000 in California alone), only 2,100 took the offer. These Filipino immigrants had been encouraged to move to work and live here. They built their lives here and would not give them up.

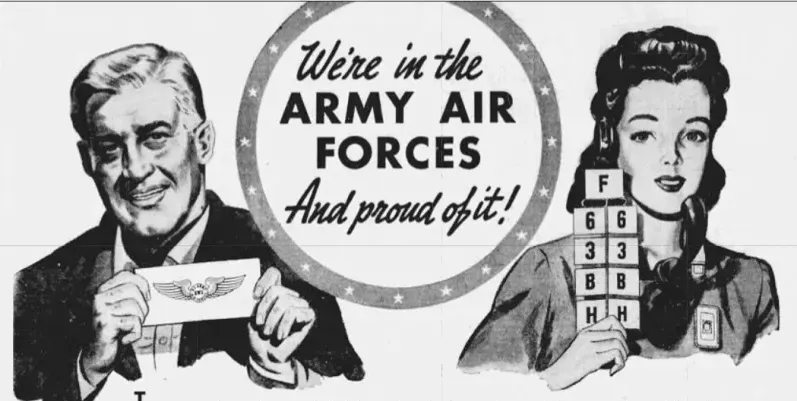

With the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the US entered World War II. Filipino immigrants—even after the bigotry they had faced here—wanted to fight for their adopted country. The amendment of the Selective Service & Training Act permitted non-citizens to enlist. Still heavily segregated, the War Department activated the 1st Filipino Infantry Regiment in 1942, with another regiment activated a few months later. After the conclusion of the war, over 10,000 Filipino American soldiers were granted citizenship, as were the wives they married in the Philippines, thanks to the War Brides Act and the Alien Fiancées and Fiancés Act.

Following the war, the Filipino community grew in size and influence throughout the San Joaquin Valley. Many acquired farm operations through their new land ownership. With farm properties abandoned due to the internment of Japanese Americans, financial assistance was made available to Filipino farmers looking to fill the void. With the formation of the Filipino Farm Center in Lathrop in 1941, Filipinos had an additional resource in promoting their farming interests and as a safe space for gatherings and events. The designation of Manila Road as a public highway created an easier access to the center, opening the door for a variety of events to take place there until its demolition around 1968.

In the decades after, Filipino Americans would face a variety of ups and downs in the country. The Luce-Cellar Act of 1946 would enable Filipino immigrants to become naturalized citizens. California became the first state to repeal its anti-miscegenation law, ending the prohibition of interracial relationships and marriage. The Hart-Cellar Immigration and Naturalization Act abolished quotas on immigration, increasing Filipino migration. However, the Filipino community in Stockton was dealt a tragic blow in the 1970s when the construction of the crosstown freeway disrupted “Little Manila,” the area that had once been home to the largest Filipino community in the United States.

Since then, the Filipino community has continued to persevere with the creation of the Filipino American National Historical Society (FANHS) Museum and the Little Manila Foundation. Thanks to the work of FANHS and Filipino American leaders like former Little Manila Executive Director Dr. Dawn Mabalon and filmmaker Dillon Delvo, the Mariposa Hotel, the Rizal Social Club, and the Little Manila District were named some of the nation's most endangered historic places in 2003. Additionally, the University of the Pacific completed its Little Manila Virtually Recreated project in 2021. This project provided a virtual reality recreation of historic Little Manila in its prime.

(For those wishing to visit the FANHS Museum, please contact them at 209.932.9037 as they are by appointment only.)

Moreover, Filipino culture is scattered throughout Stockton’s city limits, especially its fine cuisine. Spots like Papa Urb’s Grill, Pampanga’s Bakery & Restaurant, and Island Gourmet Restaurant & Market serve delicious Filipino food that will have your mouth watering.

Stockton is a place where inclusivity is a key component. Rediscovering our past and educating ourselves builds an accepting future of different creeds and colors. Stockton's foundation strengthens as we learn, accept, and unite. A future built on trust and respect for all people who visit and all who reside here.

The historical information, statistics, and photos above were graciously provided by the fine historians at the San Joaquin County Historical Society & Museum and the Filipino American National Historical Society. We appreciate everything they do in preserving our history and displaying it for all in our community to witness and learn from.

Have questions about Stockton or looking for recommendations? You can message us 7 days a week for assistance on shopping, dining, and things to do in and around Stockton.

Follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Pinterest, and TikTok - and be sure to use #VisitStockton during your visit!